A Touch of Technology

Writings from Alex

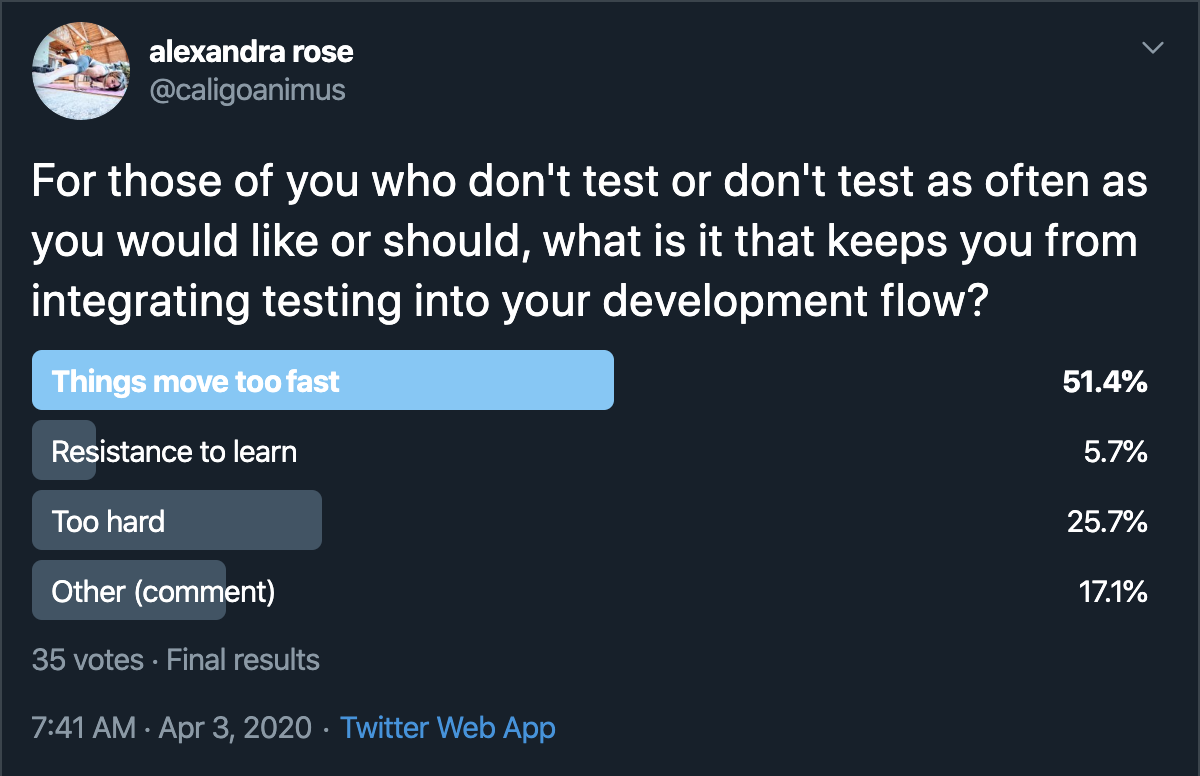

Tests can sometimes be an after-thought for developers, but what is holding these developers back from implementing tests? Is it a fast-paced startup culture that is constantly demanding of features and deadlines? Is it their natural human resistance to learn something new? 1 Or maybe the developer is just more interested in visual progress and doesn’t see that kind of success in testing?

Earlier this month I asked developers why. The answers weren’t much of a surprise.

I’ve had the pleasure to work with many different clients, but their stories about testing can often sound familiar. Businesses can move fast; management pressure to perform can cause us to avoid our inner conscience that might be telling us to test better, or to test at all.

Having worked on many teams that skirt testing in lieu of feature development, I’ve found that addressing just a few small steps in the testing process can rapidly improve a developers ability to test.

TDD?

How should you test? There have been many different “best” testing philosophies over the years, but at the end of the day the right one is the one that works best in your development flow and for you. There are many different types of developers out there and consequently many different ways to identify, solve, and test problems.

TDD stands for “Test-driven development” and often begins with defining the tests before beginning to write the software. This is a popular testing philosophy that has been passed around, in recent years especially. However, TDD requires to define one’s parameters for a piece of software first and then write the software such that the parameters pass.2

TDD sets extremely high standards; to clearly identify parameters on a first go is just setting developers up to dismiss testing all together, simply because the most popular testing methodology does not work for them. How can you write clearly defined tests when even business doesn’t know what they want?

Unfortunately, this approach is still missing a natural part of the process. The reality is that most organizations rely on a symbiotic relationship between the engineering team and the business stakeholders defining the requirements. Depending on the organization, the business stake-holders may define requirements quite well and still miss critical edge cases or technology considerations that the developer is expected to infer or inquire about.

There is an interchange between testing, building, tweaking, and retesting that takes place in any software development process. The ideal testing methodology is one that accomodates that process.

In a sense, testing software is the reverse of the traditional scientific method, where you test the universe and then use the results of that experiment to refine your hypothesis. Instead, with software, if our “experiments” (tests) don’t prove out our hypothesis (the assertions the test is making), we change the system we are testing.3

Unit v Integration v Acceptance testing

What kind of test is necessary? The definitions and lines between types of testing can sometimes be blurred, and that is true of implementation as well. In general, from more contained to more complete system testing, the order is:

- Unit testing

- Integration testing

- Acceptance testing

- End-to-end testing

The best-case answer is that all of these should be utilized to build a robust and thorough test suite for your system. However, that may be asking a lot of an organization or developer that doesn’t have any tests to begin with.

When introducing a team to testing, either for the first time or on a more intimate level, I begin with Acceptance tests. Acceptance tests are great for translating business requirements to tests and are the easiest to implement since they reflect the system one is testing completely.

Acceptance Tests

For example, I will use an Ember web app.

Introducing acceptance tests to an Ember app means testing that system on its own: the user flow, the interactions anticipated, and the results expected.

- How is the user going to use the web application?

- What is the correct way to use the system?

- What are the edge cases?

- What should not work?

Ember acceptance tests are isolated to themselves and should not interact with an external API. Each acceptance test loads the entire app. This is beneficial because it tests the system as a whole. There are times when a test may fail, not because the parameter is incorrect, but because of an unanticipated interaction with another part of the system. These tests can verify parts of the system you may not have even accounted for in your testing directly, which is helpful and necessary.

Because of the holistic nature of acceptance tests, they have been shown in my experience to be the best start in the testing story for most organizations. These tests are often 1:1 with business requirements and user stories, making them straight-forward to implement and directly addressing business’ needs.

Integration Tests

I will continue to use the Ember web app as an example.

Integration tests are somewhat isolated, testing multiple components together. For Ember, they avoid spinning up the entire application on each run. When building new features or complex user interfaces, an integration test may be a better use-case.

As your test suite grows, tests will take longer and longer to run. Being able to test different paths in a faster fashion may be of interest and this is where Integration tests can come in handy.

Unit Tests

Unit tests are as isolated as it gets. When using a unit test, no other piece of software should be included other than the subject of the test.

In the Ember example, testing individual functionality of Models, Template helpers, and utility methods, would be well suited to Unit tests since they typically wouldn’t need other parts of the app to be tested. If a Model has a series of computed properties dependent on its attributes, you could test that those CPs are able to accommodate any number of attribute values, and behave as expected.

Mirage

When introducing testing to an organization, I recommend starting with Acceptance tests. Business requirements for different user flows can be translated into testing parameters within the system, and only that system. Using the Ember app example, this means testing only the Ember app without the connection to the API.

So how do you test the Ember app with different flavors of data, and all the nuances of Ember Data without having a backend? This is where Ember Mirage comes in handy. Mirage allows you to quickly mock out all the API endpoints the browser tests may need. It uses Pretender to intercept XHR Requests from the browser tests and respond in a predictable way.

Outside of Ember, Mirage is available for other JS Frameworks as well as Mirage.js.

Mirage provides great foundations for mocking an API. It comes out-of-box with the ability to quickly use shorthand methods for request methods for each model type, and the ability to provide responses in JSON:API spec without having to do anything custom.

To give a preview of what the configuration looks like for some Mirage handlers, let’s use an example of a community gardening app that has neighborhoods, users, gardens, and messages.

export default function() {

this.namespace = '/api/v1`';

this.get('/neighborhoods');

this.get('/neighborhoods/:id');

this.get('/users');

this.ger('/users/:id');

this.get('/gardens');

this.get('/gardens/:id');

this.post('/gardens');

this.put('/gardens/:id');

this.delete('/gardens/:id');

this.get('/messages');

this.get('/messages/:id');

this.post('/messages');

this.put('/messages/:id');

this.delete('/messages/:id');

}

This is the configuration required to define the available handlers for those model types.

Having worked with Mirage on several different projects, I’ve come to find there are some small additions to the core functionality that make a huge impact on testing productivity. They can be the difference between “It’s too hard” and a nice set of tests for that new feature.

Pagination

Mirage provides a great foundation, and also the ability to grow and customize your mocks as you may need. Each handler is passed the schema and the request object to work with.

this.get('/users', (schema, request) => {

// ...

});

If you’re working with any number of records, it is likely you’re working with pagination. While you may need to tweak the code to fit the way your organization is doing pagination, the same holds. I put my paginate helper in mirage/helpers/paginate.js and then import it into the /mirage/config.js or a handler file.

Handler:

this.get('/neighborhoods', (schema, request) => {

let neighborhoods = schema.neighborhoods.all().models;

let results = new Collection('neighborhoods', neighborhoods);

results = paginateResults(results, request);

return results;

});

Paginate Results:

/**

* Split the results based on pagination parameters

* and add any meta data the frontend might be expecting

*

* Expects `page[size]` and `page[number]` on the `request.queryPrams`

* Expects the results Collection`

*

* Returns the paginated Collection with meta data added

*/

export default function(results, request) {

let pageSize = request.queryParams['page[size]'];

let pageNumber = request.queryParams['page[number]'];

if (pageSize && pageNumber) {

pageSize = Number.parseInt(pageSize);

pageNumber = Number.parseInt(pageNumber);

let start = (pageNumber - 1) * pageSize;

let end = pageNumber * pageSize;

results = results.slice(start, end);

}

results.meta = {

'record-count': results.length

};

return results;

}

Serializer:

import { JSONAPISerializer } from 'ember-cli-mirage';

export default JSONAPISerializer.extend({

serialize(resource) {

let json = JSONAPISerializer.prototype.serialize.apply(this, arguments);

// Add metadata, sort parts of the response, etc.

json.meta = resource.meta;

return json;

}

});

We add the meta to the Collection results in the Mirage handler, but we have to pass it through on the serialize.

Sorting

Lists that use pagination will also often supply sorting functionality. This is another crucial peice to supporting testing with Mirage.

Handler:

this.get('/neighborhoods', (schema, request) => {

let neighborhoods = schema.neighborhoods.all().models;

let records = sortRecords(neighborhoods, request);

let results = new Collection('neighborhoods', records);

results = paginateResults(results, request);

return results;

});

Sort Records:

import { camelize } from '@ember/string';

/**

* Sort the records array based on the sort parameters provided on

* the request

*

* Expects `sort` and `direction` on `request.queryParams` object

* Expects the model records array returned from Mirage schema lookup

*

* Returns the sorted array of records

*/

export default function(records, request) {

let sort = request.queryParams['sort'];

if (sort) {

if (sort[0] === '-') {

records = records.sortBy(sort).reverse();

} else {

records = records.sortBy(sort);

}

}

return records;

}

Filtering

The final support to add to Mirage to make the testing story better is filtering. Filtering is quite specific to the handler, so it isn’t as easily abstracted to a utility method like sort and pagination were. It is possible to abstract it out, but then you would have to check types in order to pick the correct comparison. I’ve found its easier in this situation to just write in the filtering I need for each handler.

In this contrived example, the user is able to search neighborhoods by name, or find neighborhoods with a certain number of community gardens. There are much more complex situations you’ll probably encounter with filtering, so this is a simple example. It successfully demonstrates applying multiple filters to a collection, and uses reduce to apply each filter and return the concentrated results.

Handler:

this.get('/neighborhoods', (schema, request) => {

let neighborhoods = schema.neighborhoods.all().models;

let records = filterRecords(neighborhoods, request);

records = sortRecords(records, request);

let results = new Collection('neighborhoods', records);

results = paginateResults(results, request);

return results;

});

Filter records:

const filterRecords = function(records, request) {

let filters = [];

let name = request.queryParams['filter[name]'];

let gardensCount = request.queryPrams['filter[gardensCount]'];

if (name) {

filters.push(neighborhood => neighborhood.name.match(name));

}

if (gardensCount) {

filters.push(neighborhood => neighborhood.gardens.length >= gardensCount);

}

let results = filters.reduce((results, filter) => results.filter(filter), records);

return results;

};

Visual Diff Testing

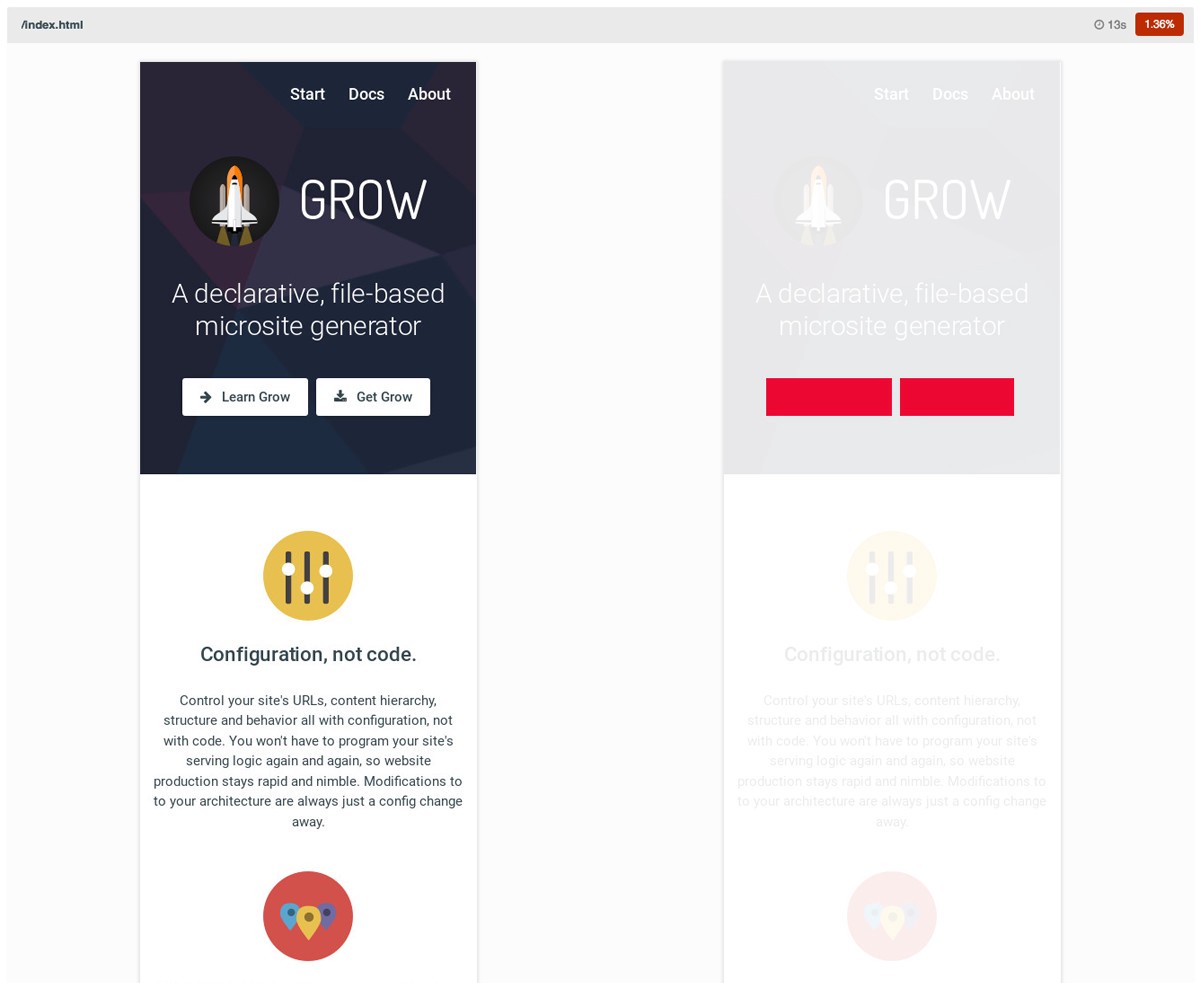

Visual testing provides some different angles to testing. For applications that rely strongly on user-experience and design, Visual testing can be a first line of support. For other applications, it can be yet another line of defense against regressions, bugs, and mistakes. Often times a written test could pass but visually be wrong, and visual diffing can catch this. It can also be a way to include testing in your codebase without having to write much in the way of tests. While I would strongly urge to use this method in tandem with typical testing, it does provide some assurances on its own.

One example tool for this is Percy. Percy works off snapshots and does a side-by-side comparison to your last build to determine if anything has visually changed. Percy can be configured to take snapshots at different breakpoints and be included in your continuous integration solution easily.

Conclusion

The biggest hurdle to any project is getting started, but the only way out is through. I strongly encourage you to get any level of testing into your code base now. The longer you wait to do so, the larger your application will grow, and the more daunting the task will seem. To get even a surface layer of testing into your code base will provide benefit.

And if you’ve never tested before, it is amazing what kind of relief having a test suite can bring. Regressions do not magically “reappear” with a new release, because you wrote a test for that regression. You can rest assured when pushing code that your additions had no ill side-effects. You can be confident when business reports a bug that this is new and not related to something long-before fixed.

Bringing testing into your development process will be beneficial to your own state of mind as well as the state of the project, so don’t hesitate.